Machine learning helps predict endangered plant species

There are many organizations monitoring endangered species such as elephants and tigers, but what about the millions of other species on the planet — ones that most people have never heard of or don’t think about? How do scientists assess the threat level of, say, the plicate rocksnail, Caribbean spiny lobster or Torrey pine tree?

Currently, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature — which produces the world’s most comprehensive inventory of threatened species (the “Red List”) — more or less works on a species-by-species basis, requiring more resources and specialized work than is available to accurately assign a conservation-risk category to every species.

Of the nearly 100,000 species currently on the Red List, plants are among the least represented, with only 5 percent of all currently known species accounted for.

But a new approach co-developed by Bryan Carstens, professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, used data analytics and machine learning to predict the conservation status of more than 150,000 plants across the globe. The results — published Dec. 3 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — suggest that more than 15,000 of these species likely qualify as near-threatened, vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered. The study was led by Ohio State alumna Tara Pelletier (PhD, 2015), now an assistant professor of biology at Radford University.

Carstens, Pelletier and their team built their predictive model using open-access data from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility and TRY Plant Trait Database. Their algorithm compared data from these sources against the IUCN Red List to find risk patterns in habitat features, weather patterns, physical characteristics and other criteria likely to put species in danger of extinction.

“What this allowed us to do is basically make a prediction about what sorts of conservation risks are faced by species that people haven’t done these detailed assessments on,” Carsten said. “This isn’t a substitute for more-detailed assessments, but it’s a first pass that might help identify species that should be prioritized and where people should focus their attention.”

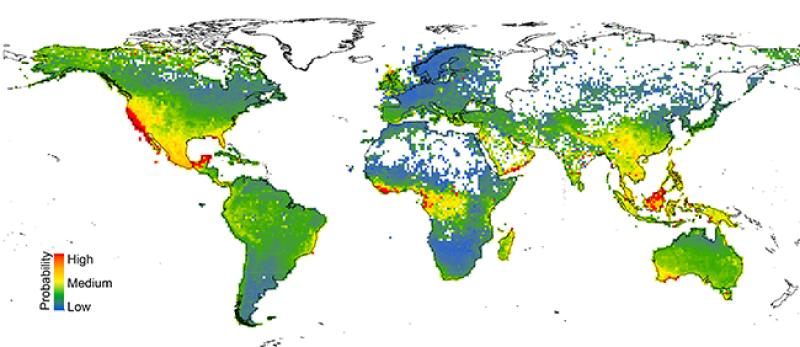

A map of the data shows that at-risk plant species tend to cluster in regions with high native biodiversity, such as southwestern Australia, Central American rainforests and southeastern coast of the U.S., where more species compete for resources.

Image courtesy Anahí Espíndola and Tara Pelletier.

Carsten said the biggest challenge was collecting data on such a large scale, noting it took several months of quality-control checking to ensure the team was working with reliable figures.

The new technique was created to be repeatable by other scientists, whether on a global scale like this study or for a single genus or ecosystem.

“Plants form the basic habitat that all species rely on, so it made sense to start with plants,” Carstens said. “A lot of times in conservation, people focus on big, charismatic animals, but it’s actually habitat that matters. We can protect all the lions, tigers and elephants we want, but they have to have a place to live in.”

This story was adapted from a university news release. Research collaborators not mentioned in this article include Anahí Espíndola of The University of Maryland and Jack Sullivan and David Tank of the University of Idaho.