Art alum Matthew Failor finds home, family as Iditarod musher in Alaska

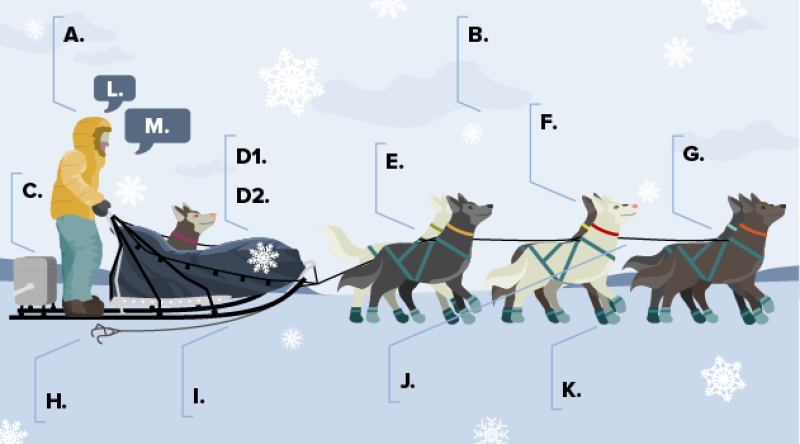

Matthew Failor (top) and his wife, Liz Raines Failor, out with their sled dogs. All photos courtesy Matthew Failor.

In 2013, Matthew Failor knew it was time to forge his own path.

The 2007 Ohio State art graduate had just completed the Iditarod – the famous Alaskan sled dog race – for the second consecutive year. Instead of continuing to compete with dogs owned by his boss, mentor and four-time race champion Martin Buser, Failor believed he had the opportunity to start his own kennel.

When he founded his 17th-Dog kennel that year, he found inspiration from his alma mater.

“I’ve always been fascinated with Ohio State as a program,” Failor said from his Willow, Alaska, home in late January. “They’re regarded as good, great, excellent at everything they do. Whether it’s gymnastics, the art program or the Wexner Center, everything they do they try to be in an elite category. We have to figure out a way to copy that culture, even if it’s on a small sled dog scale.”

Currently training for his 10th Iditarod in March, so much has changed for Failor since he decided to blaze his own trail in 2013 after his first feature in ASCENT.

He’s now a veteran musher with 53 dogs to his name. He’s moved up the race rankings, finishing as high as 13th in 2018. The Iditarod even brought him a wife and now business partner in Liz Raines Failor, a former Anchorage-based television reporter who left journalism to found the tourism business Alaskan Husky Adventures with Failor in late 2020.

“Looking back on the last eight years, I would say we knocked it out of the park,” Failor said.

FROM MIDWEST TO THE NORTHWEST

A native of Ashland County, Failor’s initial plan for an Ohio State degree was to start an art business with his older brother Ryan. Ryan would handle painting and drawing for the business, and Matthew would provide photography using skills he learned while earning his bachelor’s degree in fine arts photography.

That all changed when he took a summer job in the Alaskan capital, Juneau, in 2006. Failor always had a passion for the outdoors, and he and both of his brothers are Eagle Scouts. The prospect of making money outdoors in a far-flung locale appealed to him, and Failor spent his summer as a dog handler in Juneau.

When he returned to Columbus for the fall semester, he had a new friend in tow: Fionn, an Alaskan Husky. Fionn (pronounced “fee-OWN”) became his constant companion – even visiting the set of ESPN’s College GameDay with him. With Fionn, Failor had a built-in excuse to return to Alaska.

“Taking on a dog solidified the fact that I was going to keep going back to Juneau because they allow dogs in that work environment,” Failor said. “So it was easy to go back and forth from Ohio State to Juneau, Ohio State to Juneau.”

Clockwise from top left: A young Failor and Fionn, his first dog; an older Fionn in Alaska; Failor's custom "Just Married" sled from his 2020 wedding; Failor with a new litter of puppies from 2020.

And return he did. Failor graduated from Ohio State in 2007 with his photography degree, but Alaska kept calling him back for summer work with dogs. During the colder months, Alaskan job opportunities dry up with tourists staying in warmer climates, so Failor would go back to Ohio in the winter.

He tried to find ways to bring Alaska to the Midwest with him, dreaming of a business where he used Alaskan Huskies as an educational tool for Ohio children. His connection to dogs was so strong that he started looking for full-time work handling Transportation Security Administration dogs or military bomb-sniffing dogs.

In 2010, still seeking a clear career path, Failor decided to pack up his life and move to Alaska permanently. After completing the nearly 4,000-mile drive and then immediately selling his car, Failor landed a job with Buser at his Happy Trails Kennels. Failor had seen the Iditarod in previous winter trips to Alaska, but working directly under a four-time Iditarod champion was the first time Failor had entertained the idea of mushing.

“A couple months after working there, [Buser] asked me if I would be interested in running the Iditarod one day,” Failor said. “That question, just a very simple question, changed my whole perspective. That all of a sudden became the goal.”

Mushing in a sled dog race in Alaska is about finishing with the fastest time, but it’s also about taking care of your animals. Veterinarians along the race path will ensure the dogs are healthy, happy and hydrated. Running dogs in a way that harms their health will get a competitor disqualified.

To earn a spot in the Iditarod, mushers have to complete a series of qualifying races that can take two full years, measuring their racing abilities and dog-care skills. With that long of a timeframe ahead of him, Failor got to work.

By 2012, Failor had completed all his qualifiers and got to race in the Iditarod with Buser’s dogs. Listed with a hometown of Mansfield, Ohio, Failor placed 47th and won $1,049.

From that point on, he was hooked. The next year, again with Buser’s dogs, Failor improved to 28th place and was ready to start his own kennel. He had saved enough money to buy a small “dry” cabin (meaning no running water or electricity), which became a home for the 20 dogs Buser gifted him to thank him for his service. His older brother Ryan helped design a logo for his very own kennel.

17th-Dog was born.

MOVING AND IMPROVING

Racing in the Iditarod is like having six jobs in one.

Failor isn’t just a racer, plotting out strategies for victory. He also has to be a mechanic, building and repairing his own sleds for maximum efficiency. He has to be a veterinarian, keeping his huskies healthy. He has to be a chef, making sure the dogs’ food is balanced and nutritious as they grow and age. He has to be a meteorologist, watching weather forecasts and adapting the dogs’ diets and exercise regiments to constantly changing conditions. He has to be a massage therapist, rubbing the dogs’ sore muscles after race legs to ensure a quick recovery.

There’s all that, and then figuring out how to train the dogs to get the most out of them.

“We’re always looking at practice from an Iditarod point of view,” Failor said. “Not just, ‘We’re going to go out and play with the dogs, chase some moose, look for fox.’ We’re actually looking at it from a perspective of how it will benefit us on Day 7 of the Iditarod.”

Over the last eight years, Failor’s bond with his animals has deepened; over the course of his racing career, they’ve seen quite a bit.

In 2014, they had their best Iditarod finish to that point, taking 15th place out of 49 and earning a $20,000 prize.

There was the 2016 incident where, about one-third of the way through the race, Failor accidentally gouged himself with his knife while trying to open the packaging on his second sled. Despite the trauma of seeing his own muscles peeking through his skin, he was given crutches by the small-town health aid and allowed to continue the race. The rest of the racers honored him with the “Musher’s Choice” Award for overcoming the injury.

“I must have fallen 100 times between there and Nome, but the dogs dragged my butt all the way to Nome and we finished,” Failor said.

Failor describes the 2016 incident where he stabbed his leg in the middle of the 2016 Iditarod.

In 2018, he crossed the finish line in 13th place, his best-ever showing that came just one year after placing 59th. For that performance, he was named the Most Improved Musher.

Just one year later in 2019, he got his very first victory in a sled dog race, winning the Kuskokwim 300 with a course-record time.

Last year, in maybe the wildest moment of his Iditarod career, he had to remove himself from the race a mere 25 miles from the end after wind blew water onto the trail, completely submerging his sled and making the road impassable. An Alaskan National Guard helicopter was dispatched to rescue him and two other mushers from the flood.

“Being able to finish that race where I stabbed myself, I felt like I could finish anything,” Failor said. “I had that winner’s mentality. So [2020 is] the first time in my career I never finished something. I had dreams at night that I was waking up swimming after the fact.”

The 2021 edition of the Iditarod begins March 6 in Anchorage, though the usual course is being adjusted for this year due to COVID-19 concerns. Instead of going east to west across Alaska, the race course runs from Anchorage to the middle of the state and then back to Anchorage for the finish.

With last year’s disappointing ending still fresh in his mind, Failor is training to make 2021 his best Iditarod yet.

“We have unfinished business,” Failor said. “We’re going to do extremely well. The great Michael Jordan used anything to motivate him, and that’s what we’re doing.”

Failor describes his finish to the 2020 Iditarod.

STARTING A BUSINESS AND STARTING A FAMILY

Recently, Failor has grown beyond just his abilities as a musher and dog handler. He's had some huge life moments as well.

The first came courtesy of the Iditarod. At a banquet before the start of the 2018 race, Failor – who describes himself as normally shy – got the courage to approach an Anchorage-based CBS reporter who was covering the race. He spent the next 1,000 miles thinking about Liz Raines, had his best finish ever, and formally asked her out shortly after that.

They wed in July 2020, carried away from the ceremony in a “Just Married” dog sled.

The pandemic also led to the second huge change in his life. Due to budget shortfalls caused by COVID-19, Liz lost her job at the CBS station in Anchorage. The couple had already been thinking of ways to bring their lives closer together; Liz had been commuting 90 minutes each way from Willow to Anchorage daily, a trip that wasn’t sustainable if they planned to start their own family.

So their next big move was to go into business together.

“We have the trails. We have the dogs. We have the reputation,” Failor said. “Why don’t we try to start this?”

They founded Alaskan Husky Adventures in late 2020 to provide their spin on a dog sledding experience. They’re also offering wedding packages at the kennel, using photos of their own ceremony as marketing material. And Failor’s brother Ryan once again provided artwork for the new business’ logo.

They’ve already had their first customers, and despite being a world away from his alma mater in Columbus, Failor is getting to use that photography degree. He brings his phone with him on every excursion with a guest, and he knows exactly how to compose a picture that will make a lasting memory.

“We can get the big mountain in the background, their faces in the foreground, the dogs are smiling,” Failor said. “We’re capturing a moment that is a dream come true for a lot of people: to be dog mushing in Alaska.”

Matthew Failor, living the dream.

A frosty Failor out on the trails.