The Ohio Field School: Student research on-site in Scioto County

Folklore isn’t all old wives tales and urban legends — it’s about documenting cultures and communities here and now. That’s why the Center for Folklore Studies (CFS) at Ohio State has been conducting an ongoing research project through its Ohio Field School, which focuses on Scioto and Perry Counties in Appalachian Ohio.

Since summer 2016, CFS students, faculty and staff have been building relationships with core community partners in both counties and developing archival projects that support, document and preserve local culture. Here is just a glimpse of this work.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

Near the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio Rivers in the rolling foothills of Appalachian Ohio is the Shawnee State Park Lodge. Inside, Ohio Field School (OFS) staff and students spread butcher paper over banquet tables, assemble easels, check mics, queue PowerPoints and stock buffet tables.

It’s a big day for the OFS, a collaboration between Ohio State’s Center for Folklore Studies and community partners in Portsmouth, Ohio. After two years of conducting folklore fieldwork in Scioto County, the OFS is in its early stages of curating a traveling exhibit designed to spark conversations centered around creative placemaking. Today, participants have invited local collaborators to provide feedback and think creatively and critically about contemporary life in Scioto County.

The more than 50 attendees are a diverse set of community members spanning generations, race, class and gender, with people coming from both rural and urban regions in the county. They are engaged, first, in a short activity identifying three words they want to hear said about their community and three words they don’t want to hear. Positive words include “friendly,” “history” and “beautiful.” Negative words included “poverty,” “drugs” and “crime.”

This fall event is a hallmark of the OFS mission: to collaborate as a means of understanding how people see and create within their communities, and to facilitate conversation and give people a reason to gather.

.dailypost {background-color:#000; padding:30px;color:#fff;font-family:"capita";font-size: 1.25em;font-weight: 400;} .clicktotweet {float: right; text-align:right;}

Students who participate in @OSU_Folk’s Ohio Field School take part in a vast scope of culture-centered research and service-learning projects. #ASCDaily

ON-SITE FIELDWORK

Fast forward to spring 2018: Cassie Patterson, assistant director of the CFS, emerges from a cabin door, looking out at the trees that blanket 63,000 acres of the surrounding Shawnee State Park. Over the next half hour, Patterson’s students make their way from nearby cabins into their cars to begin their work for the day. It’s spring break, and instead of jetting off for a beachside vacation, the students in Patterson’s Comparative Studies Field School class have decided to spend their break conducting immersive research in Scioto County. Together, they document contemporary local culture through interviews, photographs, ephemera and fieldnotes. Groups of two to three students are paired with a community partner who has coordinated a service-learning project for the week.

Over the semester, Patterson and CFS Director Katherine Borland teach the students how to craft interview questions, use recording equipment, conduct interviews, take photographs and write field notes and observations. They discuss fieldwork ethics, particularly issues of representation. Integral to the course is learning about the role of archives in fieldwork, and each team of students codes, logs and deposits its materials into the Folklore Archives at the end of the term.

Once they return to Columbus, they spend the remainder of the semester learning to make their collections accessible to future researchers.Students produce a final project — what Patterson calls “a public-facing product,” such as a photo gallery or a blog post.

While on the spring break trip, students also engage in folklore fieldwork to learn about what kind of fieldworker they are — something Patterson encourages them to reflect seriously upon: When do they write best? How do they need to prepare in order to be able to listen fully? What personal frameworks and prejudices do they bring with them to the field? This reflexivity, Patterson hopes, will give her students the confidence to take on similar projects in the future.

“My sense from the students is that they are delighted to figure out who they are in the field,” said Patterson. “These students have space for self-discovery, and they get to take that knowledge with them afterward.”

In spring 2018, students engaged in four service-learning projects that were directed by community partners:

Charlie Birge and Zoe Enciso-Edmiston worked with the Portsmouth Area Arts Council and its production of “Willy Wonka Jr." The council is a vital resource for Portsmouth, where economic neglect and precarity limits artistic opportunities for kids.

Frank Isabelle and Anping Luo spent a week pulling invasive species across several counties with Josh Deemer, Southern District preserve manager for the Division of Natural Areas & Preserves at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

Molly Todd, Ana Mitchell and Luna Luo assisted with the restoration of local poet Brian Richards’ letterpress print shop, Bloody Twin Press. (You can check out original printings from the ’80s and ’90s at Ohio State’s Rare Books & Manuscripts Library.)

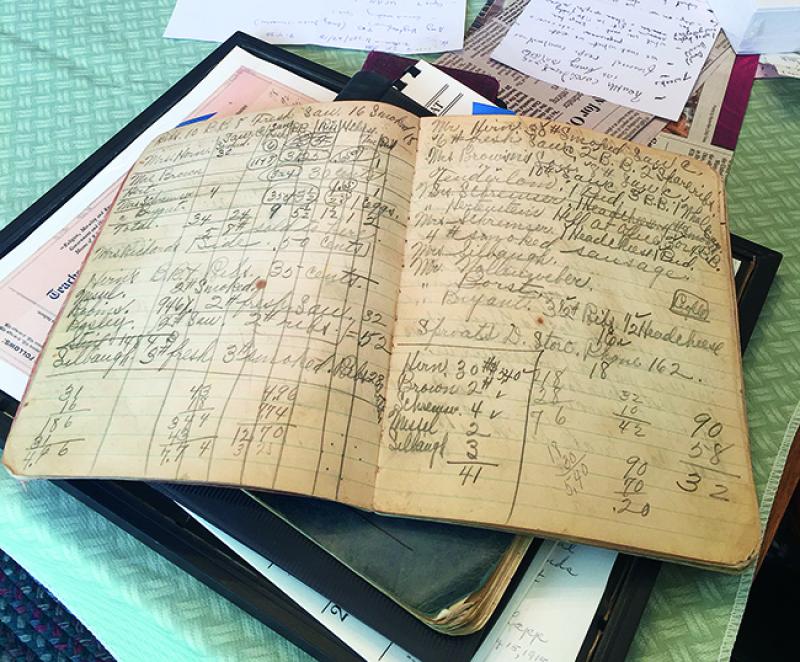

Mariah Marsden and Laura Thomas carried out a project, “Farm Books,” with Barb Bradbury of Hurricane Run Farm near Otway, Ohio, to digitize ledgers and letters from her grandmother’s farm in the 1930s, as well as the family farm’s current records.

In Patterson’s class, students also consult with local scholars and activists to learn about how they curate their own histories, culture and lives. For instance, the class listened as Andrew Feight, a digital history professor at Shawnee State University and creator of the website Scioto Historical (go.osu.edu/sciotohistorical), explained the history of segregation, desegregation and the African American community in the Portsmouth area — the location of a now infamous conflict over the desegregation of a private pool, Dreamland. Feight recently hosted the first annual Visualizing Appalachia conference, where multiple presentations explored the power of local representation. (Check #sciotocounty, #digitalappalachia and #tellourownstories on Instagram.)

On the last day of field school, students visited the home of local renaissance man Andrew Carter, a DJ, rapper, soapmaker and community activist who runs a small animal farm east of Portsmouth. They fed alpacas, petted goats and toured his property as he shared his plans to develop a youth homesteading program. Carter will join Patterson this fall at the annual American Folklore Society meeting, where he will discuss his use of Facebook Live as a tool for community activism.

The mission of the OFS is to provide students with hands-on experience documenting culture — both past and present — to understand how people maintain a sense of place in changing environments. Patterson and Borland are the enduring backbone of this effort: a service-learning and community engagement project that is not limited to the semester class. As such, they set up this multiyear research project in order to build long-term, sustainable relationships with community partners. This allows them to address community-identified needs, as well as build their archival collection, deepening and enriching it over time.

“The goal is to have an integrated project that addresses the need for students to have ethnographic and fieldwork training, at the same time that it supports the community’s needs and cultivates meaningful and mutually reciprocal relationships,” Patterson said.

The full Ohio Field School Collection is available at four public locations in Scioto County, including the Portsmouth Public Library, the 14th Street Community Center, Shawnee State Park office and Shawnee State University.

COMPLEX ENGAGEMENTS AND REPRESENTATIONS

The detailed portraits of life in Appalachia created through this work are important because this region of America tends to be misunderstood.

The declaration of the opioid epidemic as a national public health emergency, and, before that, the detailing of the epidemic’s hold in places like Portsmouth in Sam Quinones’ book Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, brought fraught attention to places like Portsmouth. While Quinones’ book drew much-needed international attention to this issue, an unintended consequence is that the first thing most people now associate with the region is drugs.

In reality, the stereotypes of Appalachia are far less compelling than the complexities on the ground, and the OFS seeks to help portray this region by engaging this complexity from the expertise of the people who know it best.

The reductive view of this region and the people that live there is a sensitive subject to Scioto County residents, and many wish that outsiders had a broader view that included the recovery programs they have in place. Locals like Whitney Folsom-Lecouffe, who works at Ascend Counseling and Recovery Services, recently curated an exhibit of an art therapy project created by people in recovery. “Canary in the Coal Mine: Escaping the Opioid Crisis” provides a space to visualize the systemic nature and the personal experiences of addiction.

Noting the sensitivity of these issues, Patterson and Borland developed the OFS model to embody sustained investment in the community that fosters trust through collaborative process and, in return, allows them to curate a complex, dynamic and living portrait of a place.

“Portsmouth, Ohio, is reaching a turning point. It’s been on the precipice of significant cultural change, this last two or three years especially,” said Nicholas Sherman, a service provider for Portsmouth’s Creative Cult Coalition. “I’m thankful there’s a group from outside the area who can look at what’s happening more objectively, document and discuss the good things to come.”

FOLKLORE IN THE WORLD

Like the Appalachian region, the study of folklore is also frequently misunderstood. While the study of folklore does in fact include old wives’ tales, urban legends and folk art, it is much broader in its scope than many realize. The American Folklore Society defines folklore as “the traditional art, literature, knowledge and practice that is disseminated largely through oral communication and behavioral example. Every group with a sense of its own identity shares, as a central part of that identity, folk traditions — the things that people traditionally believe (planting practices, family traditions and other elements of worldview), do (dance, make music, sew clothing), know (how to build an irrigation dam, how to nurse an ailment, how to prepare barbecue), make (architecture, art, craft) and say (personal experience stories, riddles, song lyrics).”

The Friends of Scioto Bush Creek, a local organization dedicated to maintaining and improving water quality at the Scioto Bush Creek, says that the OFS “has already gotten the ideas flowing, and hopefully the community leaders will keep the skills they’ve learned to improve our community and make it stronger for future generations.”

By Avery Samuels and Breanne LeJeune of the Department of English