PhD student dives into sea anemone research

PhD student Heather Glon has trouble keeping her head above water — mainly because her research requires her to travel around the world diving for sea anemones.

Glon, who joined the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology (EEOB) in 2016, is attempting to gather a globally representative collection of Metridium, a type of sea anemone that thrives in the northern Atlantic and Pacific oceans. By looking at relationships between genetics and geographic distribution, she hopes to understand how and why the anemones have evolved over time.

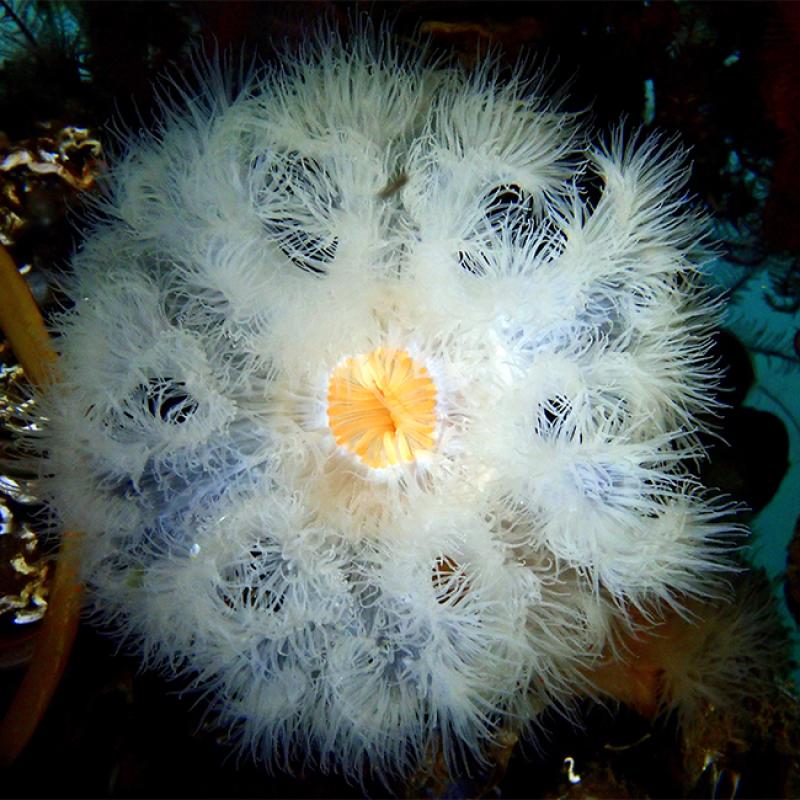

“It’s a very variable group of sea anemones in terms of how it looks — it can be fat or skinny; big or small,” Glon said. “Divers love it because it can be really striking when you see a whole bunch of them together.”

They may look like vibrant, underwater gardens — sea anemones are actually named after the “anemone” flower — but Metridium is far from plant life. Covered in venomous cells, the marine animals spend their days patiently waiting for fish and other small organisms to swim close enough to become trapped in their toxic tentacles (check out the work of Glon’s advisor EEOB Professor Meg Daly on sea anemone venom).

She is looking at genetic data from the anemone samples she’s acquired, in addition to those collaborators have sent her, “to determine which species came from which oceans originally; how much connection there is between both sides of the Atlantic; how many total species there are, etc.,” she said. “There are a lot of questions that we’re looking at.”

Most recently, Glon and Daly took their anemone hunt to Iceland off the coasts of Reykjavik and Hjalteyri.

“We have really good representation from both sides of the Atlantic, but nothing from the middle, so we needed to fill in that huge gap. Iceland was hugely important to sample,” Glon said.

The team began their Icelandic excursion by looking for Metridium growing on manmade surfaces like piers and floating docks — where the anemones can nearly always be found.

“These guys really like hard substrate, so rocks and docks and piers and everything else. They don’t do well in sand,” Glon explained.

Glon checking for sea anemones on a dock in Ireland.

But Iceland presented a different picture. The team didn’t find Metridium on any floating docks, “which was really weird,” Glon said. “They weren’t as prevalent in other locations that we’ve been to, but hopefully the samples still show some interesting relationships.”

She eventually collected samples from about 20 anemones, all obtained while diving.

How she gets the samples? “I have a tiny spatula,” she said, laughing. “It’s plastic so it doesn’t rust, and I just attach it onto my suit.”

She then puts the fragments in plastic bottles and preserves them in alcohol until freezing them at the Museum of Biological Diversity, where she extracts the DNA. So far, she hasn’t noticed much genetic diversity between different Metridium populations in the Atlantic Ocean.

“Our preliminary data shows that Metridium is carried around a lot by ships,” she said. “Anemones from New Hampshire and Norway look almost the same — there isn’t a lot of differentiation. So there’s obviously been a lot of movement.”

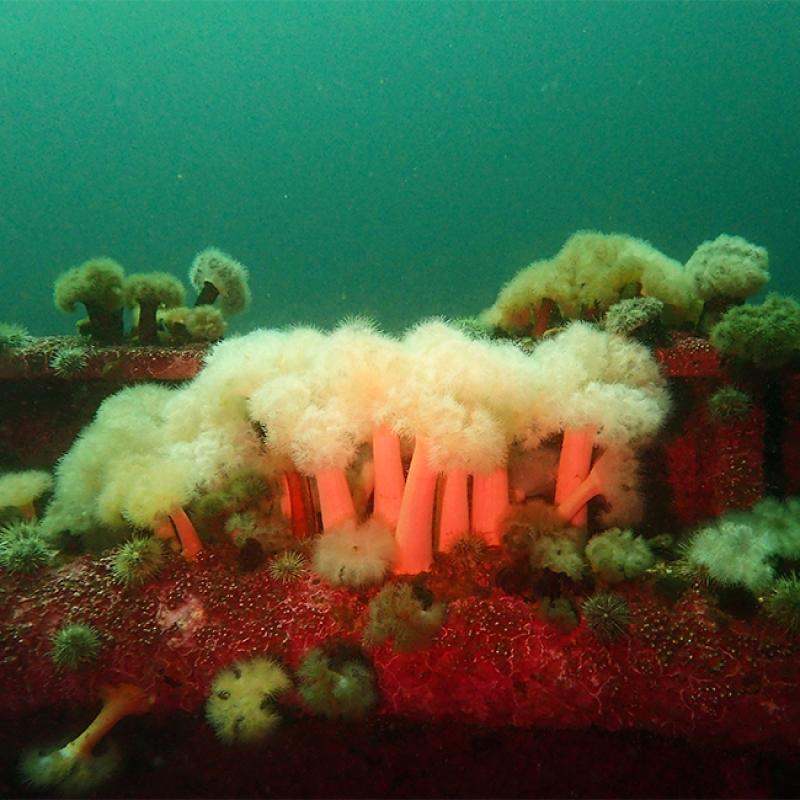

Metridium growing on a shipwreck in Newfoundland, Canada.

A few other hypotheses she and Daly have explored center on “refugia,” or areas where communities of organisms survived during the Last Glacial Maximum circa 19,000 years ago, despite surrounding regions being covered in ice.

“That started as a big question when we were starting and it’s turning into a lesser question,” she said, adding that she plans to finish her work on the Atlantic Ocean samples this year before sending her data for further analysis. “Hopefully we can start getting some good answers for what’s going on.”

Glon, who hopes to complete her Metridium research by 2021, earned her BS from Palm Beach Atlantic University and MS from Central Michigan University before coming to Ohio State. A lifelong love for wildlife has led her to work as a tropical aquarist, a butterfly garden interpreter and a full-time volunteer at a seal rescue and rehabilitation center, just to name a few. She’s also pursuing a graduate minor in public policy and management through the John Glenn College of Public Affairs to hone her passion for communicating with the public about biodiversity.

“I wasn’t planning on doing a PhD, but then this opportunity came up with Meg and I was totally on board, because it combines the methods that I’m interested in and the organisms that I really want to work with,” she said. “So I came here, and even though it’s not near the ocean, it’s perfect.”