'Sonder' introduces gaming tech to film world

The short film “Sonder” flows between the aesthetics of 2D and 3D animation to share the story of Finn as he tries to move forward when a relationship comes to an end. At times, the characters, environments and their textures appear flatter (think 90s Disney, Rick and Morty or Studio Ghibli). At other times, the way the lighting, reflections and movements respond to one another creates a depth and realism unique to 3D films (think new Disney/Pixar movies).

“It’s a very different kind of technology to create an animation. I had never done it before, and I didn't even think it was possible,” said Swearingen, who has worked on films like “WALL-E,” “Ratatouille" and “Toy Story 3.” “We were literally starting something that nobody had done before. People didn’t think was possible to make animation, especially beautiful animation, using real-time rendering.”

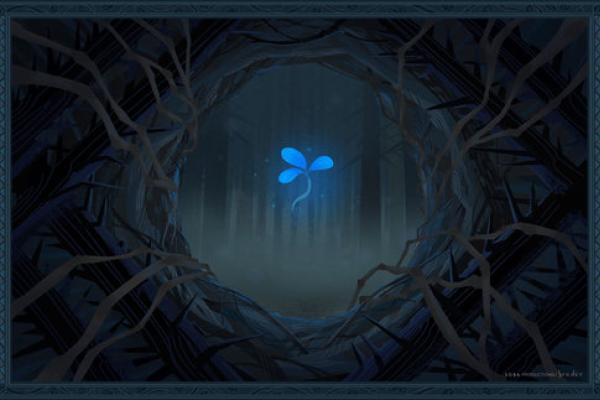

A scene from "Sonder" illustrating various animation elements blended to create the film, which explores the intensity of emotions following the end of a relationship.

Rendering is the process of taking information held in a 3D environment — like objects, textures and lighting — and compiling them into pixels that make up the 2D image projected on a screen. Traditionally, animators have used different strategies for rendering 3D films versus video games. Films tend to utilize rendering techniques that create incredibly detailed and realistic images, but the trade-off is that it requires massive amounts of time and computer processing power to generate a single image, Swearingen said.

“When I was working on ‘Cars 2,’ one frame took hours to render,” she said.

“Sonder” will be screened at the Wexner Center for the Arts on Nov. 14, with a Q&A with Swearingen, Director Neth Nom and Technology Supervisor Andrea Goh following the screening.

In contrast, because video games require user input to determine what happens on the screen, they need to have the ability to generate and render the corresponding images fast enough to simulate movement. To do this effectively, video games use alternative rendering processes that work “in real time,” meaning they can generate at least 24 two-dimensional frames per second.

The “Sonder” crew sought in 2015 to create a film using a real-time rendering game engine called Unity3D, a process that was faster, cheaper, more efficient and more accessible than conventional animation. However, using a game engine also created challenges. The three-dimensional environments needed to take up less data and memory for the program to work, and certain conventional tools, such as some lighting tools, were unavailable.

Swearingen said these aspects of the game engine necessitated a completely different look and a new way of lighting: She would manually shade each shot to match what the lighting was supposed to look like instead of relying on software to calculate the lighting in each frame. It took almost three years to finish the film, but Swearingen said the opportunity provided her with valuable experience working with an all-remote team using innovative technology that she predicts will become a trend in animation.

“I learned many new methods for collaborating on a large scale, which is something that I practice in my own work every day with my other collaborators,” she said. “Also through ‘Sonder,’ I gained great insight into development pipelines for real-time game engines and have applied this to my own work and research, which focuses on visual storytelling in games and animation for social good.”