Arts and Sciences APIDA community reflects on Atlanta killings, anti-Asian racism

Activists at a rally against Asian hate at the Ohio Statehouse on March 27. Photo courtesy Paul Becker/Becker1999.

The March 16 killings in and around Atlanta targeting Asian women was an appalling and catastrophic display of misogynist, racist violence, but for many in the Asian and Asian American community, it was not wholly surprising.

From the U.S.’s hostile political and economic conflict with China to aggressive anti-Chinese rhetoric from leaders regarding COVID-19, anti-Asian sentiment nationwide has been on the rise.

The social advocacy group Stop AAPI Hate reported nearly 3,800 incidents of anti-Asian discrimination from March 2020 to February 2021, acknowledging that many more incidents went unreported. In a recent Anti-Defamation League survey gauging harassment on social media, Asian Americans represented the largest year-to-year rise in online harassment — 17% compared to 11% last year. In a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center before the Atlanta killings, 42% of Asian Americans say Asian people in the U.S. face “a lot” of discrimination. On March 31, a 38-year-old man was arrested on hate crime charges after a video of a verbal and physical assault on a 65-year-old Asian woman in New York City went viral on social media. He reportedly yelled, “You don’t belong here,” during the violent attack.

The Atlanta shootings at three Asian-owned spas in which eight individuals — including six Asian women — were killed is far from the first attack targeting the Asian Pacific Islander Desi American (APIDA) community. For many, the shootings are a predictable result of America’s anti-Asian transgressions — past and present, evident and obscured.

Find op-eds and statements created and curated by the Arts and Sciences APIDA community here

“This rhetoric used by the former president, making it seem like the Chinese government deliberately caused the virus, it was a factor,” said Minseon Ku, a PhD student in the Department of Political Science. “[The killings] were shocking, but at the same time, they weren’t shocking because it was something we all were waiting to happen.”

Pil Ho Kim, an assistant professor of Korean in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, said, “Asian hatred and racism go back centuries. The virus was a good excuse to beat up on China and incite animosity toward Asians.”

In a written statement endorsed by Asian American scholars affiliated with the program, director of Asian American Studies Pranav Jani wrote, “For scholars of Asian American history, culture, literature and ideas, informed by decades of scholarship in ethnic studies, feminism and queer studies, we have an added task beyond calling for empathy: to remind the Ohio State community that although these incidents are horrific, they are not at all uncommon or unexpected.”

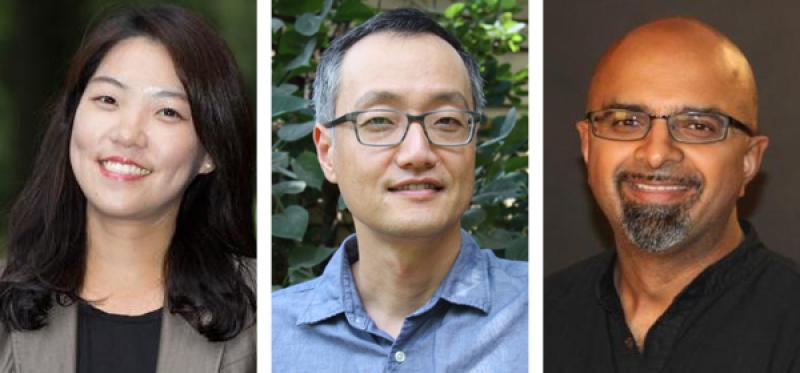

From left: Minseon Ku, Pil Ho Kim and Pranav Jani

Ku’s PhD specialty is in international relations and political psychology, and her research focuses on states’ social constructions of threat and national security. She was born in South Korea and spent her childhood in Singapore before returning to Korea to attain a bachelor’s degree in political science and international relations and a master’s in international cooperation from Yonsei University.

Ku began her PhD program in 2017 and experienced unsettling and frightening microaggressions, hostilities and provocations early and often near campus. She lived just south of campus in a small apartment off High Street. Walking to the grocery store, she would regularly get harassed by people driving by, and men would accost her and ask bizarre and offensive questions — like if she was from China, if she had a boyfriend, if they could have her phone number or if she was interested in a part-time job. The encounters were constant, and Ku ended up moving as a result.

Though she can’t be sure to what extent her race played a part in all these disconcerting interactions, Ku quickly became hyperaware of how she stood out as an international student from Korea in a sea of predominately white people.

“Whenever I go to the grocery store, I do get the sense that people look at me — like old white men glaring at me,” she said. “There’s a heightened sense of sensitivity on my part. … There’s an unfamiliarity with Asians that makes me feel like I stand out wherever I go. That visibility makes me uncomfortable at times.”

Ku’s experiences and feelings of exclusion are related to her research in international relations and political psychology. One aspect of her work studies how citizens tend to form beliefs and attitudes based on their leaders’ foreign policy stances. How much is racial prejudice in the U.S. influenced by international policies and the rhetorical discourse behind those policies? For Ku and many others, whether prejudice and policy are related isn’t the question. It’s a matter of how much one factors into the other.

“My hunch is that there needs to be more awareness of how U.S. leadership uses its language against other countries,” she said. “That definitely has implications on the domestic level.”

Kim focuses on contemporary Korean society and pop culture. He was born and raised in South Korea, earning his master’s in sociology from Seoul National University and his PhD in sociology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Kim has lived in the U.S. for more than 20 years and began teaching at Ohio State in 2014.

As news in Atlanta unfolded, some of Kim’s relatives contacted him, warning him not to go outside.

“Whatever way you cut it, this is a racially motivated killing, and the targets were these marginalized Korean and Asian immigrant communities,” Kim said.

Those communities were further marginalized in the immediate aftermath of the killings. The suspect, a 21-year-old white man, was located about 150 miles south of Atlanta and was taken into custody with incident after a brief vehicle chase. In a press conference, sheriff’s department Capt. Jay Baker paraphrased what the suspect told investigators about his motives, saying, “He was pretty much fed up and kind of at the end of his rope, and I guess it was a really bad day for him and this is what he did.”

The conference, along with the discovery of Baker’s previous anti-China sentiments on social media, led to intense criticism and shook confidence that the killings would be investigated as hate crimes. Many voiced anger and frustration that the suspect’s account was able to drive the narrative away from intersectional motives where racist and misogynistic stigmas overlap.

“In terms of this investigation, everybody was outraged,” Kim said. “The way this deputy, who I would characterize as a racist for his past behavior and the way he framed things, stigmatized those victims, it’s just disturbing they try to steer the discussion into that.”

Kim continued, “On the other hand, I was heartened by people’s reactions across the country. Even in Columbus, there were rallies. There’s quite a bit of discussion about the broader picture of violence toward Asians and Asian Americans in this country.”

A rally against anti-Asian racism at Bicentennial Park on March 20. Photo courtesy Ce Shang

Alongside his role as director of Asian American Studies, Jani is also an associate professor in the Department of English whose research examines postcolonial studies and ethnic studies. When he sat down the day after the killings to write a statement for the Asian American Studies website, he was struck by the burden of his words and what he wanted them to convey.

For Jani, calling attention to how racism, white supremacy, and gender and sexuality discrimination and exploitation entwine was challenging.

“It was difficult to write,” he said. “I wanted to accurately represent not just anti-Asian racism in the sense that this was one part of a long history of racism, but also to make sure it was intersectional and that questions of gender and sexuality were very much part of what I was writing.”

Jani doesn’t want the conversation to end here. He recently helped facilitate a guest commentary series in The Columbus Dispatch, connecting Ohio scholars and activists to write op-eds for the publication and widen the scope of awareness. The larger goal is to further more discussion and action, ensure APIDA voices aren’t erased or relegated, and connect the history of anti-Asian racism in the U.S. to a better understanding of how white supremacy has habitually harmed BIPOC groups. At Ohio State, this means helping bridge gaps and cultivate interdisciplinary collaboration across other college units and departments working in these spaces.

“How do we understand these as tied together so we strengthen all of these movements?” he said. “How do we make it more than just a momentary interest? That’s been an area of focus.”

***

In July 2020, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced that international students attending schools could not take a fully online course load in the fall semester and remain in the country. International students were suddenly faced with the prospect of departing the country or transferring to another institution to avoid the initiation of removal proceedings.

Ohio State signed on to an amicus brief challenging the decision, relayed assurances to its international student population and joined other universities in opposing the policy proposal. Though ICE reversed its planned rule, Ku felt its message. She felt it loud and clear.

It told her she wasn’t welcome because of where she was from.

“That’s when it made me really feel like I’m not welcome,” she said. “It’s the country that makes you feel really unwelcome. You can’t shake off that feeling — the feeling that I’m expected to leave even though I’m here legally. It was as simple as that.”

Four months later, Joe Biden was elected president of the U.S. Some people wondered if America’s racist, anti-Asian sentiment would die away with the advent of a new administration.

“I was like, ‘No. Once it’s made salient, it will stay there,’” she said. “The fact that I hold different citizenship means I’m regarded as a potential threat to the American society. … I always have to be on the lookout for myself. The fact that I’m Asian, that I look Asian, my appearance, that I’m different from the majority of people around me, that puts me in danger.”

The horror in Atlanta proves Ku right.

Activists displaying their signs and messages at a rally against Asian hate at the Ohio Statehouse on March 27. Photo courtesy Jack Agrasuta

- Statement by Asian American Studies director Pranav Jani on Atlanta killings

- Statement by School of Communication on Atlanta killings

- Statement by Ohio State's Office of Diversity and Inclusion

- The Lantern: Resources, guidance about anti-Asian racism following Atlanta shootings

- The Columbus Dispatch guest commentary series

- 'There are those who benefit from divide-and-conquer policies that see Asians as “forever foreigners' — by director of Asian American Studies Pranav Jani and director of the Center for Ethnic Studies Namiko Kunimoto

- 'I don’t feel safe.' Killings touch nerve for local Asian and Asian American women — by Meow Hui Goh, associate professor of East Asian languages and literatures

- Asian Americans long discriminated against, long fighters for rights — by English and journalism alumnus Stephen Kyo Kaczmarek, professor of English at Columbus State Community College

- Actions, not empty words, needed to dismantle systems of oppression — by Bhumika Patel, Leadership Council volunteer at OPAWL

- It is time to 'rock the boat' and make waves in the name of ending racism against Asian Americans — by Stacey Diane Aranez Litam, assistant professor of counselor education at Cleveland State University