New Course Offers an Interdisciplinary Approach to Climate Change

Climate change has been called the world’s greatest threat, and whether it’s studied through the lens of science, politics or economics, in no ways is it a one-dimensional issue.

Beginning autumn 2016, though, Ohio State students will have an opportunity to study climate change from multiple angles through a first-of-its-kind interdisciplinary course.

“Climate Change: Mechanisms, Impacts and Mitigation,” listed as EARTHSC 1911, is a new general education course that will blend perspectives on climate change from a variety of disciplines and will be team-taught by faculty in Earth sciences, biology and history.

“We need to have general education in climate change — it’s not something just for Earth science majors,” says Michael Bevis, Ohio Eminent Scholar and professor in the School of Earth Sciences. “This is one of the most important issues out there.”

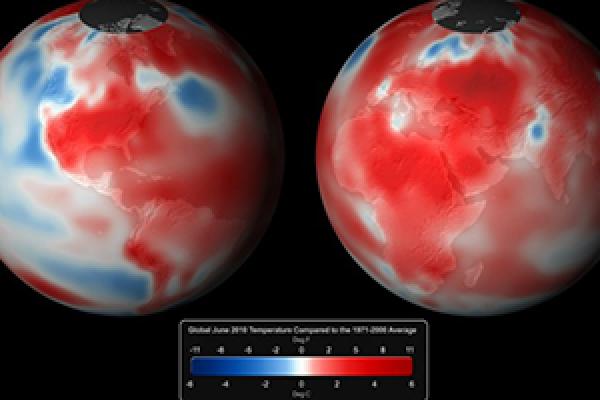

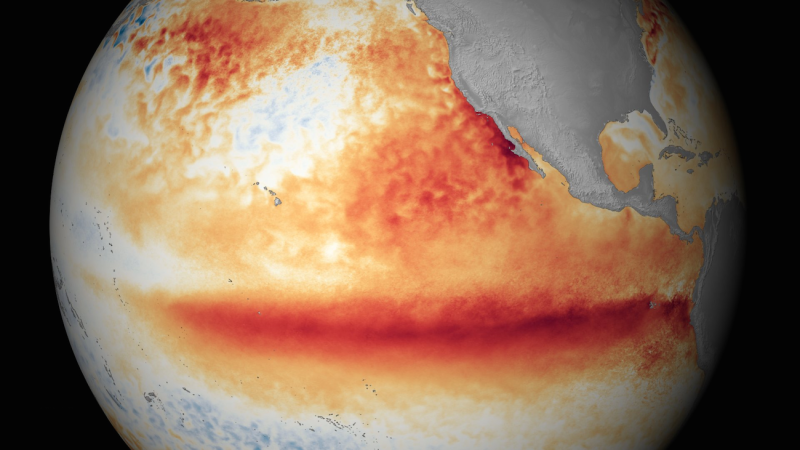

As predicted by many climate scientists in early 2015, the present El Niño, the largest since the late 1990s, poured oceanic heat into the atmosphere, adding to the global warming produced by carbon dioxide emissions. The combined impacts produced the hottest year recorded since instrumental measurements began. Image: NOAA

Course topics on climate change will include the effect of carbon dioxide; biological responses; historical experiences; effects on human infrastructure; and the implications for business, politics and policy. It is the first course in the College of Arts and Sciences to be presented by three distinct departments through a proportional credit sharing agreement, and it will fulfill one of any three general education requirements based on student selection: Natural Science (Physical Science), Natural Science (Biological Science) or Historical Study.

Bevis, who is one of the course’s faculty instructors, uses GPS technologies to study sea-level change, bedrock uplift and other geophysical events as they relate to climate change. However, he sees beyond his own immediate research focus area and says that to study climate change, “you don’t just want to talk about climatology, you want to talk about impact.”

That’s where biology comes in.

Steven Rissing, another one of the course’s instructors, is a professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology. He studies evolution, science education and the intersection of science with public policy.

“The concern isn’t just about the fate of polar bears. What happens to biological systems impacts people, and often in very unexpected ways,” Rissing says. “For example, biologists have linked climate change impacts to the spread of the Zika virus and, before that, Ebola. A 2012 report also noted that the Arab Spring was preceded by a drought of biblical proportions in the region that drove people off their farms and into already cramped cities.”

Agricultural systems are biological systems, and when they get badly stressed, the researchers say that society suffers too. Another area of concern is ocean acidification, caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which already has been causing the collapse of coral reefs and reef ecologies all over the world.

As Bevis and Rissing began constructing the course in 2014, they realized that one leg was still missing from their stool. While they can study and discuss the individual physical and biological consequences of climate change, they say it is difficult for anyone — student or scientist — to imagine what could happen when all of these consequences occur at the same time.

“I was reading the Sunday paper, and I found a review about Ohio State historian Geoffrey Parker’s book Global Crisis: War, Climate Change and Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century. This discusses what historians have called the General Crisis, a period when the whole world was at war, and when much of the world was starving,” Bevis says. “I contacted Geoffrey and said, ‘this could be our third leg!’”

In this book, Parker, Distinguished University Professor and Andreas Dorpalen Professor of European History, suggests that the Little Ice Age — the cooling period that occurred during the 17th century — was largely responsible for this global disruption.

Parker will join the course along with two other colleagues from the Department of History, Sam White and John Brooke.

White, an assistant professor of history, also studies past climate changes and extreme weather. He says that lessons in climate change from the past can inspire proper citizenship and policy decisions in the present.

“This is more than just modeling atmospheric conditions — this is a human problem,” White says. “I’ll share with the class concrete examples and narratives about how climate has affected people over time and what lessons we have learned.”

His first book, The Climate of Rebellion in Early Modern Ottoman Empire, also examined the implications of the Little Ice Age, with a focus on the Eastern Mediterranean. “During the coldest period of the Little Ice Age, you had sequences of freezing winters and droughts that not only created famine but also, as a result, political and social upheaval.”

White says that climate change certainly mattered in the past, and it certainly will matter in the future.

“I’m hoping that we can go beyond cautionary tales and gain insights that can help us bring research and policy questions to the forefront,” he says. “We live in a very different world, but there are perennial human problems that we can translate from past to present.”

Aside from the team-taught lectures, the course’s recitation sections will each include a teaching assistant from each of the three disciplines to enhance group discussions.

“I hope that through the course, students will analyze climate change from an evidence-based point of view, not a political assertion-based point of view,” Bevis says. “There are a lot of people who want to decide what’s true and what’s not true based on assertion. Our students will come out of this course and be able to judge by the evidence.”

The course’s lectures will take place on Tuesdays and Thursdays during the autumn semester from 2:20-3:40 p.m.

Top image credit: NOAA