First Person: Portrait of a young naturalist

Breanne LeJeune, program coordinator, Global Arts + Humanities Discovery Theme, shares a day of adventure and discovery with their nephew at the Museum of Biological Diversity in this first-person account.

We all travelled light, taking with us only what we considered to be the bare essentials of life. When we opened our luggage for customs inspection, the contents of our bags were a fair indication of character and interests…I travelled with only those items that I thought necessary to relieve the tedium of a long journey: four books on natural history, a butterfly net, a dog, and a jam jar full of caterpillars all in imminent danger of turning into chrysalids.” ― Gerald Durrell, British naturalist, conservationist and author

Meet Edward

When he was 4, Edward visited the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences at Western Michigan University, where I worked at the time. He sifted his grubby hands through the augmented reality sandbox in the Schmaltz Geology and Mineral Museum, ogled the massive shark teeth in the Kelley Collection and fell forever in love with fossils, minerals and creatures of all kinds, dead and alive. That was the beginning. I indulged his interest by procuring a starter-kit of specimens for him: luxurious feldspar, flaky muscovite, spindles of glimmering copper, quartz crystals, obsidian nodules and, of course, coprolite — dinosaur poop. And when he started referring to me as “Aunt Breanne, the paleontologist,” I only corrected him the first few times. It was, after all, a considerable promotion.

Today — motivated by a ravenous reading habit and educational television series like "Wild Kratts," "Planet Earth," "Blue Planet," "Lonestar Law," "North Woods Law" and our favorite, "River Monsters" — he is a young naturalist in the classic style, like Charles Darwin, Rachel Carson, Gerald Durrell and Jacques Cousteau before him. His passion for and curiosity about the natural world inspires myself and my family, all of whom have embraced his hobbies if, for no other reason, than to ensure proximity to his unrelenting sense of joy and commitment to improving the world for our nonhuman counterparts.

According to the national Center for Biological Diversity, human activities like habitat destruction and encroachment, poaching, pollution and global warming could contribute to a massive increase in extinction rates as soon as 2050. Conservation biologists work to prevent extinction and other biodiversity loss through conserving natural ecosystems, park management, educating the public, performing research and rehabilitating at-risk species so they can be returned to their natural habitats with an increased probability of survival.

And so it’s Edward to the rescue.

The Museum of Biological Diversity

If a child is to keep alive his inborn sense of wonder, he needs the companionship of at least one adult who can share it, rediscovering with him the joy, excitement and mystery of the world we live in." — Rachel Carson, American marine biologist, author and conservationist

The Museum of Biological Diversity at Ohio State is a large brick building on Kinnear Road, just 10 minutes from the academic center of the Columbus campus. When I learned Edward and his class would be visiting Columbus, I immediately reached out to Katherine O’Brien, postdoctoral researcher and outreach coordinator for the museum, who encouraged us to schedule a visit. In the weeks that followed, I shared information about Edward’s interests with Katherine, who curated a customized tour.

The Museum of Biological Diversity

Based on Edward’s fascination with dinosaurs and conservation and the fact that he lives in northwest Michigan (near the exquisite coastline of Lake Michigan), it was decided the tour would feature visits, most notably, through the tetrapod and mollusc collections. We also scheduled a tour of the Orton Geological Museum to meet Jeff, the giant land sloth, and check out the newest addition to the collection, Cryolophosaurus ellioti.

When the day finally arrived, Katherine welcomed us and ushered us through a set of heavy, wooden double-doors into the main hallway of the Museum of Biological Diversity. Once inside, the museum becomes a Death Star: its hallways are numerous and of seemingly infinite length; they unfold and unfold and unfold. Like a living landscape from "Inception" — the farther in you get, the farther you have to go. The walls are lined with educational posters, insect illustrations and vivid wildlife photography. Occasionally, a door is propped open, and we peer inside: In the Triplehorn Insect Collection, a massive, four-paneled photograph of a Hercules beetle stretches all the way to the ceiling, towering over busy researchers. “That’s life size,” I tell Edward, and his mouth falls open. “No, no it’s not.” Katherine quickly interjects.

The Museum of Biological Diversity houses seven collections and three laboratories:

- Triplehorn Insect Collection

- Tetrapods Collection

- Acarology Collection (ticks and mites)

- Crustacea Collection

- Fishes Collection

- Herbarium

- David H. Stansbery Mollusc Collection

- Dr. Carsten’s Speciation Using Computational Analysis Laboratory

- Dr. Adams’ Leafcutter Ants and Symbiosis Laboratory

- Dr. Daly’s Marine Invertebrate Diversity Laboratory

The museum welcomes visitors of all ages, but groups must be of 10 or more people, and visits scheduled ahead of time. To schedule a visit, submit an inquiry.

Tetrapods Collection

The first stop on our tour is the Tetrapods Collection (amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals), which is an important repository of Ohio and North American species and of some research expeditions worldwide. The collections were established shortly after the founding of Ohio State in 1870. Today, it houses approximately 170 amphibian, 200 reptile, 2,000 bird and 250 mammal species, which are used for research and teaching.

Undergraduate Research Assistant Grant Terrell emerges from the collection’s aisles like a specimen sprung back to life — his dark hair powdered gray and accented with a shock of white like a classic French homage to a white-winged chough. Grant is a history major with a minor in ecology and evolution. In his capacity as an undergraduate research assistant, he manages visits to the Tetrapods Collection, sets up displays, enters data, prepares museum study skins and teaches and trains volunteers.

Grant begins the tour with the reptiles; he knows this is the quickest ticket to the heart of our many young dinosaur enthusiasts. “Which dinosaur do you think might be a relative of this guy?” he asks, holding the large, bony jaw of a Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus). Edward, holding fast at the front of the pack, grows quiet, scanning his internal dinosaur database, before confidently suggesting “a Mosasaur.” “Well, yes!” Grant exclaims.

From there, Grant walks the class down the aisle, regaling them with the collection’s greatest hits.

After winding our way through towering aisles of open shelves lined with clear glass jars of snakes, frogs and turtles; wooden boxes of multi-colored bird eggs; and prepared specimens of pangolins, hawks, chickens, swans and owls, we arrive at the far corner of the collection, where specimens are stored in large, chest-high metal cabinets. Grant pulls open a deep drawer with several large birds folded onto themselves. The smell of naftolin (the active ingredient in moth balls) fills the air, and perhaps for the first time, it really hits Edward that these are dead animals. “It’s kind of sad,” he says, looking at the contorted body of an ostrich, its long neck bent back unnaturally. “You know what?” Grant responds empathetically, “It is sad.”

Throughout the tour, Grant took constant measure of his audience's interests, concerns and comfort levels, and adjusted his approach accordingly. If the students giggled at his snake factoids, he’d show them more snakes and maybe a funny turtle. If they grew squeamish at the sight of fetal frog bodies or dead baby birds, Grant would swiftly move along to something a little more friendly. In this particular moment, when Edward was suddenly very aware of and saddened by death, which is something of great weight for a 7-year-old of any constitution, Grant maneuvered with exceptional skill: Instead of carrying on with the tour, he paused, acknowledged and shared Edward’s sadness, and engaged him, with the respect you would give a peer, in a difficult but important conversation about death and its unfortunate but necessary role in museum curation and scientific research.

“It’s important that we have these animals because it provides evidence that helps us learn,” he explains to Edward, before walking the class over to the body of a large black vulture. “For example, this bird got a giant piece of plastic stuck in its crop, and we know that because it’s still there. It’s important that we have this so we have a record of this type of thing happening.”

Check out the Instagram story about this vulture here.

The David H. Stansbery Mollusc Collection

The Division of Mollusc is divided into two major collections housed in separate ranges. The bivalve collection consists of about 78,000 catalogued lots, mainly composed of North American freshwater mussels. The gastropod collection (and a small amount of material of other molluscan orders) consists of about 20,000 catalogued lots, primarily North American freshwater snails. The collections are among the largest in the world for freshwater Mollusca.

Caitlin is quick to admit that the saltwater molluscs displayed near the collection’s entrance are a bit of a smoke show. They are big, they are beautiful and they do the important work of getting people into the collection and interested in molluscs. However, the real heart of the collection is the freshwater specimens. And while they may not be as glamorous as their saltwater counterparts, Caitlin makes a strong case for why we should accord them more respect and attention.

Like Grant, Caitlin has been told about the group and their interests, and she has come prepared. She leads with a surprising fact: “Did you know that molluscs are the most federally-protected animal?” she asks. “Do you know why they are so important?” I confess: I had no idea. She explains how molluscs act as filters and help keep our water clean and safe. She also explains how, if we don’t take care of our rivers and lakes, this endangers molluscs because they have to work really hard to filter out all the pollution and sometimes it is too much for them. Knowing that this curious bunch will return to northern Michigan and spend their brief but altogether glorious summers splashing and diving in those same lakes and rivers, she also teaches them how to appreciate molluscs and, perhaps more importantly, how not to appreciate molluscs by explaining what happens when you pry open their shells. “It’s like if someone broke your back,” she says, gesturing toward the shell’s hinge and surrounding ligaments.

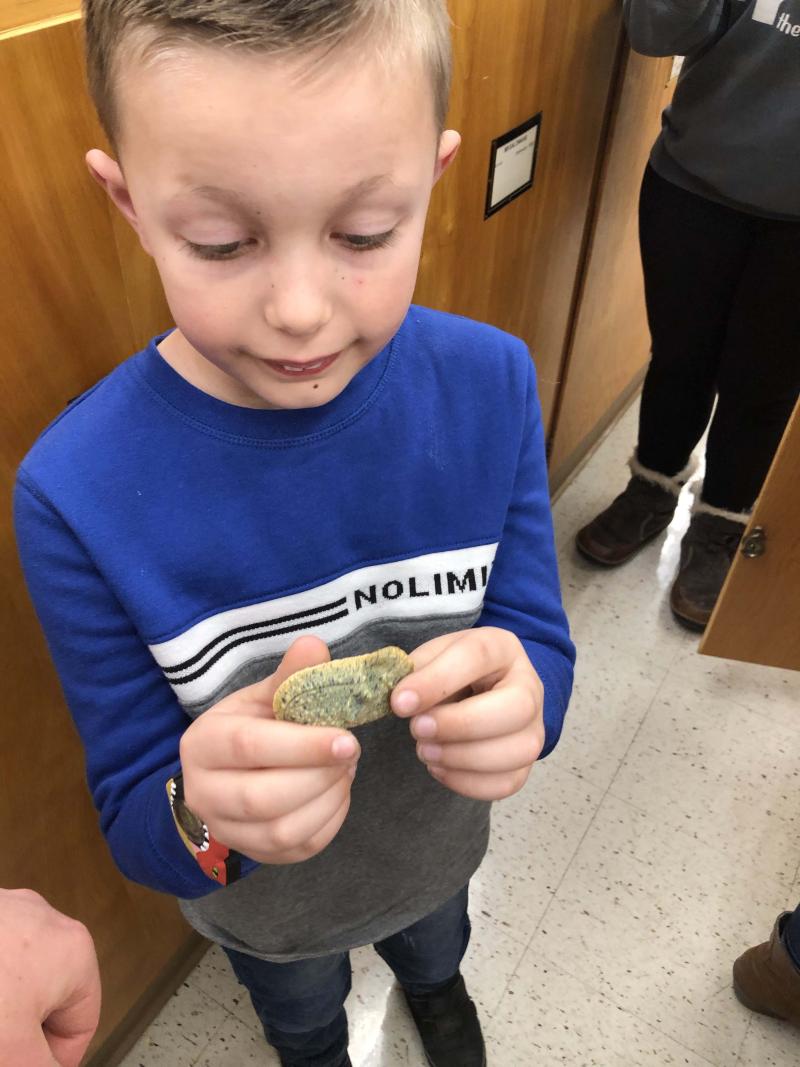

Next, she leads the group over to a pile of hundreds of small, dark shells. “Do you know what an invasive species is?” she asks. “Humans?” suggests Edward. Caitlin’s eyes twinkle. “Yes,” she says, surprised but endeared to his prematurely jaded response. “Humans are an invasive species. Do you know what these are?” she asks, gesturing to the shells beside her. “I’ll give you a clue: they are in the lakes where you live, and they are brought in by the boats.” Aha, this is an easy one. “Zebra mussels!” they chime together. As a child growing up on the coast of Michigan, you are taught to watch out for the razor-sharp edges of zebra mussels that pepper the shoreline, ripping fine tears into the soles of your feet. Over the last decade, zebra mussels invaded the Great Lakes after being brought in from Eastern Europe and western Asia on the hulls of large ships. In addition to being a nuisance for swimmers, zebra mussels have caused a wide variety of much more serious problems, including biodiversity loss, increased water transparency and the colonization and subsequent death of native mussel species. They also glom onto underwater structures like pipes, piers, docks and boat hulls and can cause significant physical damage.

The mollusc collection is an interesting counterpoint to the tetrapod collection: whereas the shelves of the tetrapod collection are full of many large, eye-catching specimens, the mollusc collection appears, at first glance, much more like a traditional library. Its residents are small and tuck neatly into the thin shelves of the collection’s many heavy, wooden cabinets. In the back, jars of snails, collection supplies, and of course more bivalves line tall metal shelves.

“The Museum of Biological Diversity is a living library,” Katherine explains. “People come here from around the state and country and study these specimens just like you would study at a book at your local library.”

In the tetrapod collection, Katherine pulls out a drawer and shows us a turkey vultur bird from 1887. “This bird is important because we only know it existed in this area at this time because someone thought to enter it into the record here.” In this and many ways, the museum’s importance to past and future Ohio is made tangible. And in the face of increasing extinction rates, natural history museums also bear another sad but important responsibility: preserving specimens of animals that have already or may soon go extinct, like the museum’s prized pangolin or enormous leatherback turtle.

For young naturalists like my nephew, the Museum of Biological Diversity taught him several hard-earned lessons about the impact humans have had on their environments and ways that we can advocate for the animals of the future.

It takes generosity to discover the whole through others. If you realize you are only a violin, you can open yourself up to the world by playing your role in the concert." — Jacques-Yves Cousteau, French explorer, conservationist, filmmaker, author and oceanographer

Want to learn more?

Free resources and events for naturalists of all ages

- iNaturalist: iNaturalist is a citizen science project and online social network of naturalists, citizen scientists, and biologists built on the concept of mapping and sharing observations of biodiversity across the globe.

- Audubon Center: The Audobon Center is a place for the public to connect with nature through a variety of opportunities — such as school-aged children learning more about the natural world and conservation, organizations meeting outside the board room, families hosting celebrations surrounded by nature or visitors enjoying the beautiful spaces inside and outside the center.

Books for young naturalists

- Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World by Rachel Ignotofsky

- The Boy Who Drew Birds: A Story of John James Audubon by Jacqueline Davies

- Girls Who Looked Under Rocks: The Lives of Six Pioneering Naturalists by Jeannine Atkins

- Life in the Ocean: The Story of Oceanographer Sylvia Earle by Claire A. Nivola

- Manfish: A Story of Jacques Cousteau by Jennifer Berne

- The Tree Lady: The True Story of How One Tree-Loving Woman Changed a City Forever by H. Joseph Hopkins

- The Corfu Trilogy by Gerald Durrell (now a TV show: The Durrells in Corfu)